The Good Project is pleased to announce that we have received over $1 million in funding from The John Templeton Foundation to study the impact of the recently developed Good Project Lesson Plans.

In the three year, mixed-methods study, we will investigate the effects of these lesson plans across a variety of educational settings and probe how engagement with the curriculum might result in student character change. In addition, participating teachers will partake in a community of practice in which they will be able to learn from one another's successes and challenges with the curriculum.

As described to the Templeton Foundation:

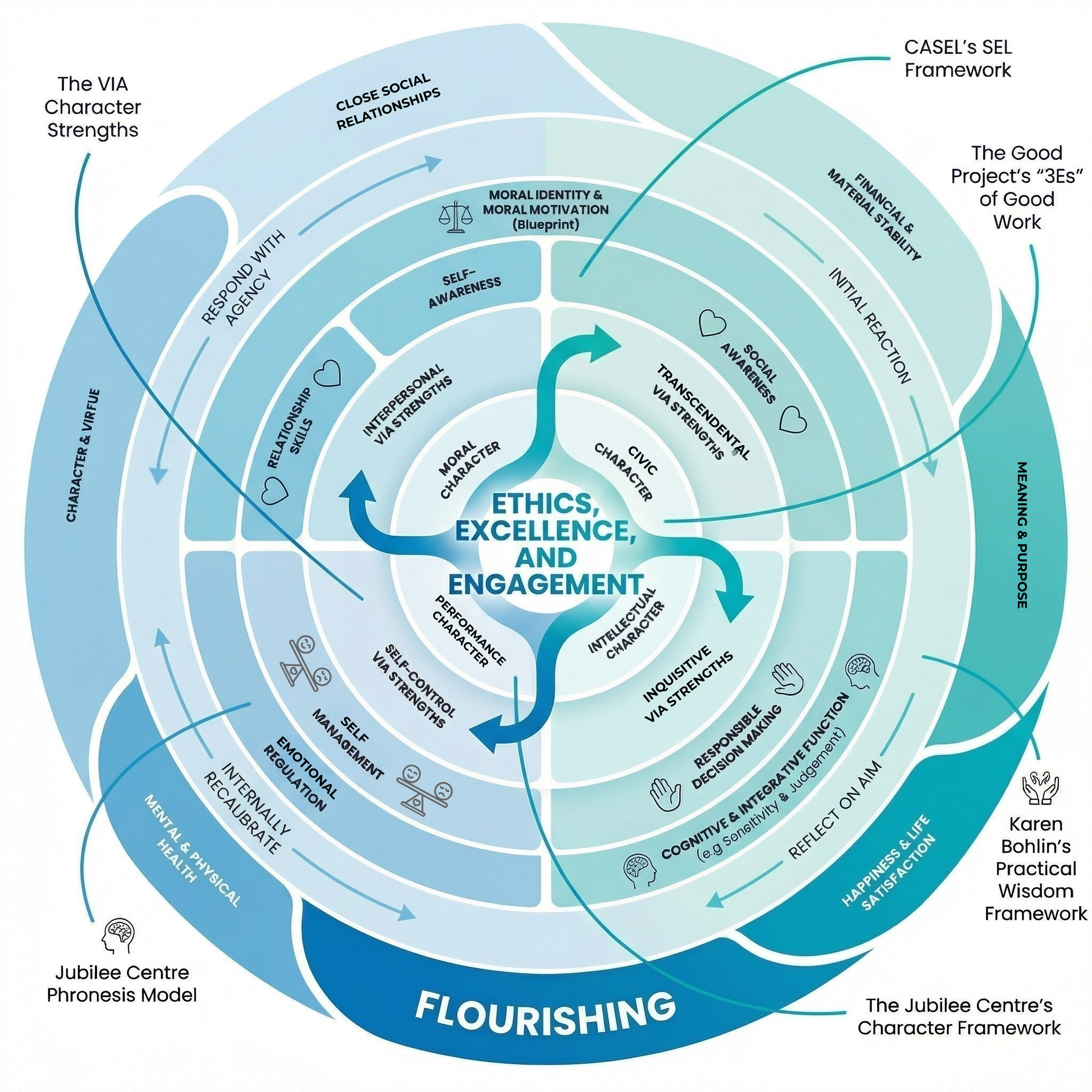

"The world of work is rapidly changing. Although adolescence is a period of identity development, few students are taught to think about how to behave ethically at the workplace. The Good Project, originally the Good Work Project (Gardner, Csikszentmihalyi, & Damon, 2001), has developed lesson plans focused on personal reflection related to workplace and school-based dilemmas. The curriculum aims to help adolescents develop and internalize moral (i.e., a good neighbor), civic (i.e., a good citizen), performance (i.e., a good student/worker), and intellectual (i.e., a good thinker) virtues. These virtues embody The Good Project’s 3 Es of good work: Ethical (for the greater good); Excellent (high quality); and Engaging (meaningful).

This mixed-methods national study will build upon current work with a diverse group of teachers who are committed to exploring deep questions about the nature of work, its connection to one’s values and identity, and its relationship to social good. In Year 1, we will use surveys, focus groups, and student portfolios to assess teacher fidelity to the curriculum and students’ potential growth in character virtues and ability to navigate complex dilemmas. In Year 2, we will adapt curricular content for teacher use and gain feedback through focus groups. In Year 3, we will focus on scalability and sustainability of the curriculum. Educators at participating schools will be led through three phases to build an online community of practice where they can exchange ideas, strategies, and materials as they implement the lesson plans. Overall, the project aims to create a community of practitioners who will help build a strong, scalable character program."

The Good Project thanks The John Templeton Foundation for the generous funding of this project. We are eager to begin and look forward to releasing announcements, lessons learned, and materials developed in the course of our research.

If you have questions regarding the study, please contact Shelby Clark, Senior Research Manager, at shelby_clark@gse.harvard.edu.