by Margot Locker

With the school year starting, we asked some of our “GoodWorkers” about their goals for the coming school year. A busy and impressive group, with many exciting plans! (To learn more about any of these initiatives, please feel free to write us at margot_locker@harvard.edu.)

Bloomsburg University, Pennsylvania:

The Bloomsburg University GoodWork Initiative is focused on advancing undergraduates’ understanding of what it means to do academic Good Work as college students as well as identifying strategies and developing resources to advance their ability to achieve Good Work. To this end, the BU Good Work Initiative seeks to find ways to integrate Good Work concepts into curricular and extracurricular activities at Bloomsburg University. We are energized by the positive response we have received from all members of our campus community including support from all Colleges (Business, Education, Liberal Arts, Science and Technology) and several key Offices on our campus (Dean of Students, Diversity and Retention, Student Affairs, Graduate Programs and Research). We will continue to develop GoodWork inspired programs, such as an “On Your Honor” conference, in the Spring of 2013.

Amy Maturin, Unity Charter School, New Jersey:

After getting acclimated with the GoodWork Toolkit last year and working, along with my 1st and 2nd grade students, to fully understand the concept of good work, I am hopeful that my former students will be implementing the conversations and vocabulary they learned last year in their new classrooms. My goal for my current class is to use the activities that we developed last year while revising with more understanding. I’m looking forward to my continued collaboration with the project and to see the conversations and understandings of a new set of children.

Design for Change, http://dfcworld.com/

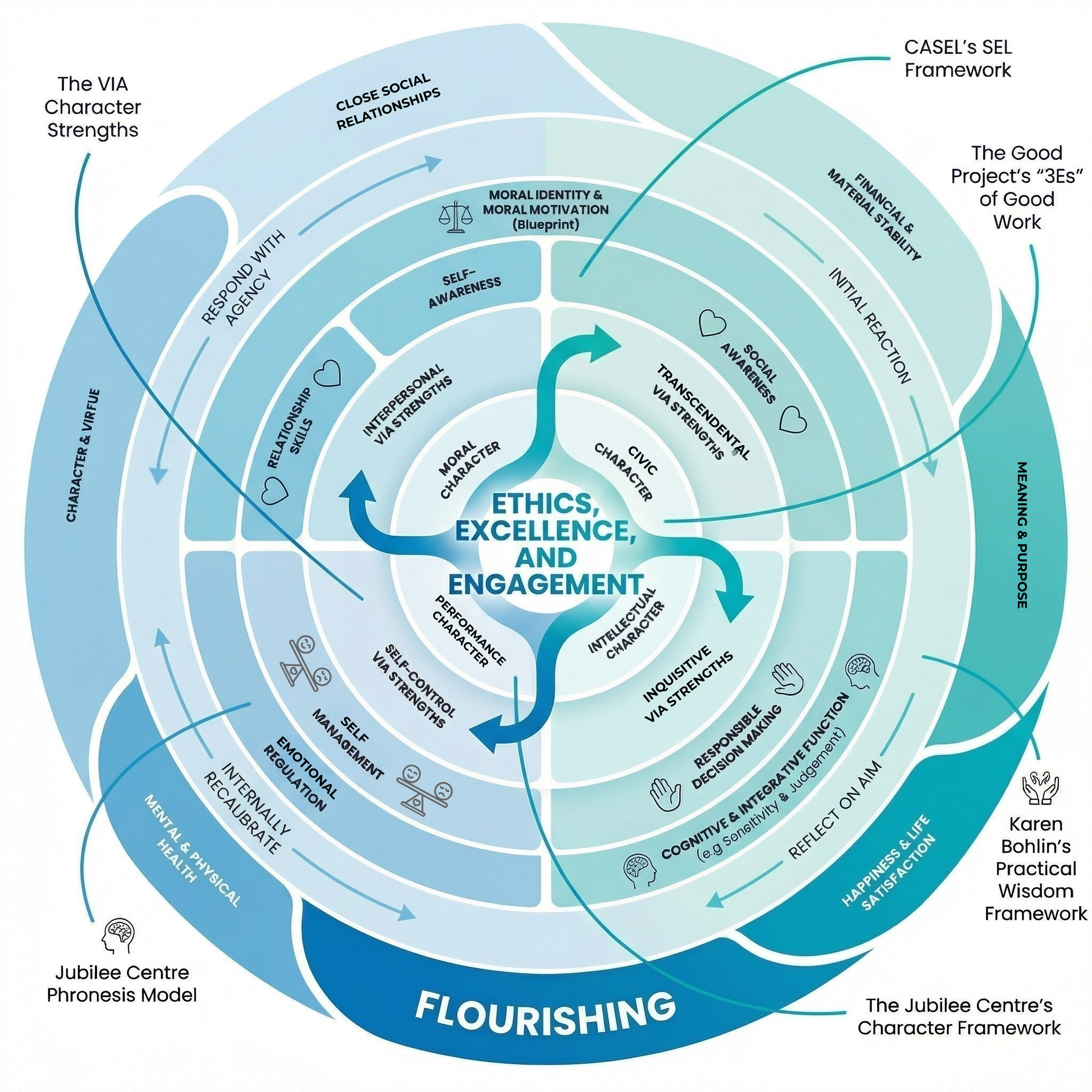

Design for Change is excited to be collaborating on a unique service learning and design thinking curriculum with the Harvard’s GoodWork Team. We have worked together to seamlessly integrate vital GoodWork principles of ethics, excellence an engagement into each aspect of Design for Change. We will be launching the curriculum this fall providing access to tens of thousands of students and teachers across 35 different countries. We are excited to share the GoodWork framework with children around the globe, who are all saying “I CAN!”

Patricia Kievlan, Convent of the Sacred Heart High School, San Francisco

I’m in my second year as Director of Community Service at Convent of the Sacred Heart High School in San Francisco, an all-girls Catholic high school celebrating its 125th school year. Our school has a long history of great work in philanthropy, and I hope to build on those existing partnerships with significantly more opportunities for direct service to our community here in San Francisco. Our students and faculty are eager to find new ways to serve: we do a lot of talking about needs in our community, one student said, but we don’t take a lot of action. This year, the 40 students in the Service Learning elective course will be planning new service activities on campus and will lead the charge for getting their classmates actively involved in their community on a weekly basis. We hope to use guiding questions from the GoodWork Toolkit (What constitutes GoodWork? Why is it important?) to inspire, guide, and evaluate the activities that we lead this year.

Ewa Suchecka, University of Warsaw

I work inthe Department of Education at the University of Warsaw. In my program there are 260 people – teachers and University students. The teachers are our students’ tutors from elementary schools, where they do their practices. I hope this year to give them the overview of GWP, (based on “Good Work. When Excellence and Ethics Meet.”, but also a little from “5 Minds for the future” and some articles on GoodWork from the website. On the basis of some narratives the participants will discuss what good work means to them, they’ll come up with their own definitions of GWanddiscuss the three Es, with the final goal to refer them to their own lives.I’ll also guide them to refer the 3 Es to the 4 major learning goals from the Toolkit.One of my goals is to guide them how to transfer what they’ve learnt about GW to implementing these ideas to children, in other words, to consider how to teach GW to children.

Deborah Coney, Bellevue School District

My goal as a 3rd grade teacher is to use the Good Work Toolkit to instill the E’s to my students through whole group discussion, journal writing, and sharing. My hope at the end of the year is to demonstrate growth in their understanding of the 3 E’s and developing personal tools to live by for each child.

GoodWork Team

Here at the GoodWork Project, we are excited to work with such an energetic and diverse network of teachers. This year, we hope to get a solid sense of what is working and not working in the classroom through streamlined assessment and consistent check ins with teachers using the Toolkit. We are also excited to be working with two excellent elementary school teachers on our Elementary Toolkit so we can have a completed version by the end of this school year! We are looking forward to a great year and learning from all of you!

What are your goals for this school year?