Good Citizenship Through Good Work: A personal reflection

by Shelby Clark

On average, the American worker spent 38.6 hours at work in 2019-- that is almost 2 hours above the OECD average of 37 hours per week (link). Some scholars estimate that Americans spend 90,000 hours of our lives at work (link). Given how much time we spend “on the job,” it is perhaps not a surprise that our employment often ends up serving more of a role in our lives than solely as a way of earning wages. For many, it’s a way of finding purpose and meaning (link). For others, it is a way to perfect a craft (link) or hone one’s skills. Still yet, for others, a job is a way for an individual to contribute to society and do good (link); that is, it is a way to contribute as a citizen. It is this last contention that I most wish to consider. What is the relationship between one’s work and citizenship? Below, I reflect upon my own struggle with the question of the relationship between good work and good citizenship.

When I went to college at Johns Hopkins University, I thought I was going to become a musicologist--someone who studies the history and structure of music. The summer after my sophomore year, I trekked to the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, to track down a Bach score for a faculty member who was abroad. I then spent the spring of my junior year abroad in Vienna, where I completed a musicology internship with a Gustav Mahler expert. As a sample task, I translated one of Mahler’s letters from old German into English; I spent weeks listening to Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 on repeat for an assignment. The summer before my senior year I applied for and received a grant to conduct research at the Cleveland Orchestra that would serve as the basis for my senior thesis. I sat alone in the archives--week after week after week--looking at how the Orchestra’s repertoire changed in response to WWII. In the fall of senior year, I navigated from my Arts and Sciences campus across Baltimore to the Peabody Conservatory so that I could take history of music classes not offered on my campus; musicology was not really a major offered on either campus and was instead something I had somehow convinced two advisors to allow me to pursue under their guidance. Later that year, I signed up for the GREs as I thought about applying to PhD programs for musicology. Yet, by spring of my senior year, I had applied and was accepted into several Masters programs for counseling. What happened?

Being a good citizen--one who is actively civically engaged--does not mean that you necessarily show up to vote every four years, nor does it mean that you have to be the best volunteer in your community. Being civically engaged, or a good citizen, can occur in all sorts of ways. Indeed it can be all encompassing; it is something you can be doing, or thinking about, learning about, or working towards, at any time of your day, in any location.

Besides immersing myself in classical music in college, I had also worked all four years of college in the college career center. I began by answering phones and then slowly worked my way up to being the main assistant to the internship director. I spent 12 hours of my week thinking about how college contributed to students’ career success. I pondered how students could find a job that they valued--one that would both give them a sense of purpose, one in which they would find meaning.

As I reached the middle of my senior year of college, I began to apply these questions to myself: Would I find meaning in life as an academic? Would my research as a musicologist be of value to society? In which ways? In all, would I be a good citizen if I became a musicologist?

The purpose of this blog is not to demean the profession of musicology; my musicology advisor was one of the best mentors I have ever had, and I still have the utmost respect and love for classical music and its history. My purpose is to question how we think about the connection between our work and our citizenship. For me, working in the career center, I was very aware that Americans spend a large proportion of their waking hours on their work. Having just witnessed the 2008 financial crash and the societal pathologies which had led to it, I was inspired to make sure that my work would meaningfully contribute to my wider communities and societies. At the time, I wasn’t sure if publishing in academic journals for musicologists or other historians would fit the bill. I knew that I always wanted music and history to be part of my life; but I just wasn’t sure if a life as a musicologist was going to be right for me.

How often do individuals similarly aspire to make a difference in society through their careers? In a recent survey of alumni from mission-based international schools, two thirds of respondents noted that the way they felt they were making the most impact in the world was through their job or career. Of the eleven options shown for how to make a difference, the second highest chosen was making a difference through one’s family or friends, at just under a half.[1] For example, one individual in the study made note of her attempts to make a difference through her career:

Interviewee: Yes. Well, I'm really trying as much as I can within the curriculum that I have to be that person at the school.... I really try to just be a way to broaden their horizons a little bit, and be a person in which they can see someone else than they're used to, even though I'm also from the same municipality. I grew up here and all of that, but just having experienced the things that I have, and met the people that I have and just being the person that I am being...coming back here to a place where, it's still very, like we don't really talk about it, it's still very to taboo in many ways...I try to push small change within my classes.

I'm very specific about not pushing any gender norms in my classes that I teach...they ask me a bunch of questions. Like, are you a boy or a girl? Like, does that even matter? Trying to have those kinds of things….I feel like it's my one way of creating change right now. Just trying to have these kids be slightly more open-minded than they would have if I weren't there.

And so in the music that they listen to ... or the way they think about English, maybe I can even get one person to become a little more fond of English, a little bit fond of learning languages. That would be something for me that I would have felt like I would have succeeded. So, I feel like right now my job is where I can create the most change. And I feel like I can, I feel like that's actually feasible, which is very fun, but that's also a huge responsibility.

The fact that I can change these kids' minds when they're so malleable. I feel like that's where the biggest arena [is] for that right now. And I'm obviously trying to make that a good thing and trying to use it for good.

This person is a teacher, generally a career considered to be a service to the community, but, in addition, through this career the individual is trying to change norms regarding gender and other issues. As they see it, their career enables them to be a good citizen .

By the end of my time at college, I turned to counseling as a way that I thought I could meaningfully impact society. Rather than sitting in an archive creating research, I decided that I needed to work directly with people in order to try to bring about tangible change in their lives. Within two years I had received my Master’s in counseling, with a focus on school counseling. Thereafter, I went to work as a high school school counselor in St. Paul, Minnesota. Working with refugee students as well as students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, I did feel that my work was meaningful and created some tangible impacts for some students.

Yet, by the end of two years, I knew it was time to return to my original love: research.

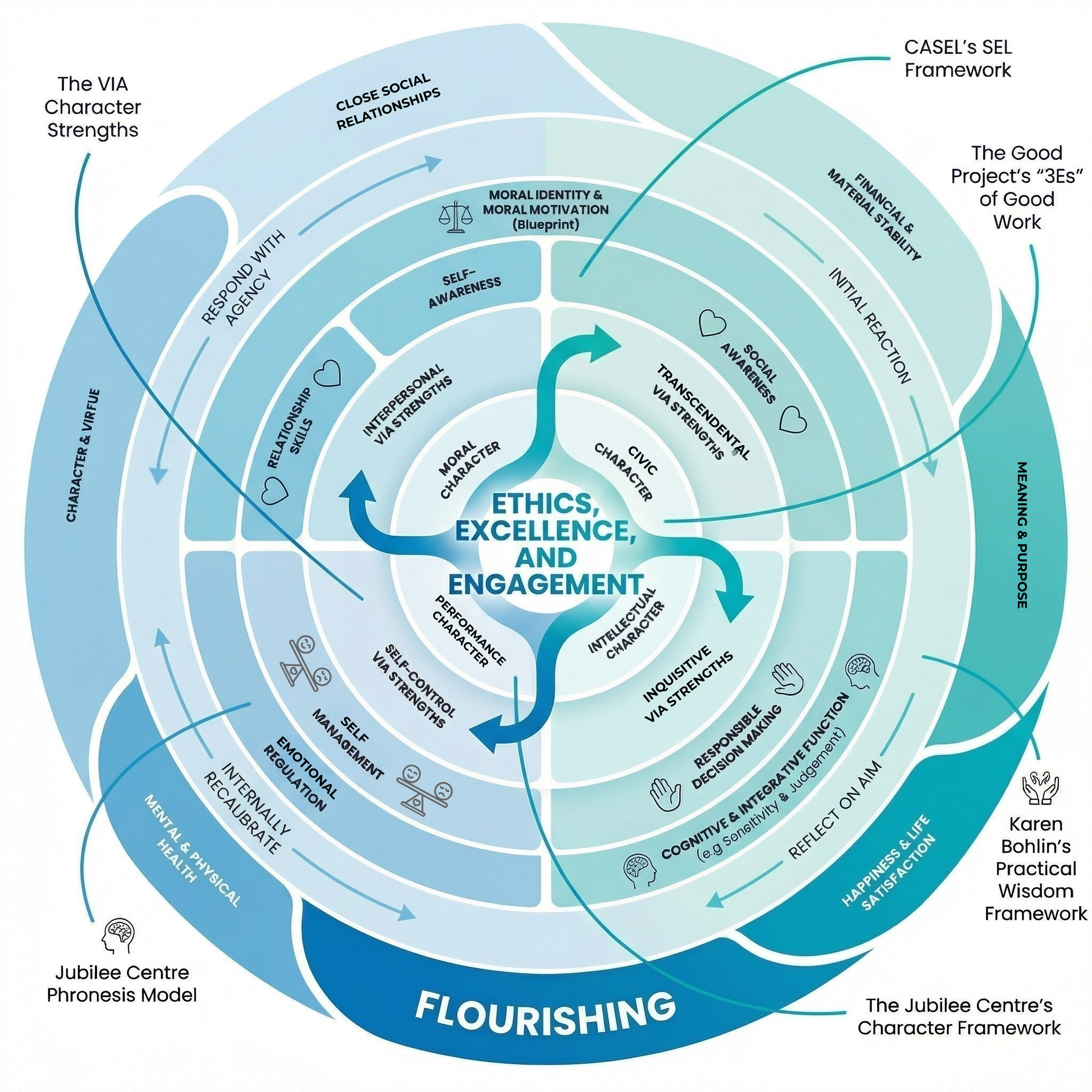

Let me apply some of our concepts to my own biography. At The Good Project, we define “good work” in terms of three attributes (the three Es): Ethical work seeks to have positive impacts on clients and on the broader society; Excellent work is high in quality; and Engaging work is meaningful and purposeful for the worker. Upon graduating from college I was so determined to contribute to society--obsessing about the ethical impacts of my work-- that I forgot about the importance of finding meaning and purpose in one’s work. This is not to say that I disliked being a school counselor, but rather that it never seemed to fit quite right. I missed research, I missed books, and I missed having a constant “purpose” when I went home at night. In terms of the three Es, I believe that I did ethical work; I hope that it was excellent in quality; but I did not feel sufficiently engaged.

I am fortunate--I was able to take a circuitous path back to my enduring love of research. By doing so, I believe that I am able to fulfill all of the 3Es of good work. Even more so, I was also able to find a way to merge good work with my initial hope of contributing to society more broadly; as such, I fulfill some of my own citizenship goals through my work.

I ultimately spent four and a half years at Boston University pursuing a Ph.D. in Applied Human Development. I learned how to use psychological principles and apply them directly to everyday educational issues (in my case, I focused on curiosity and issues of character and social justice education). After graduating, I was able to move into my current position at The Good Project. On the project, I apply psychological concepts and methods to understand educational settings better – an ultimate goal is to create curriculum and assessment materials that hold promise for improving educational practices and outcomes. I feel hopeful that the work we do can make a difference in the lives of students, teachers, educators, and, in some way, over time, influence the larger education system.

As noted above, citizenship has a tendency to become an all encompassing idea. It can mean being politically engaged (e.g. voting), or it can mean social activism (e.g. protesting climate change). For me, it means in some small way trying to contribute to creating a better and more equitable education system for all. Thus, a broad variety of choices exist for how one might go about being a citizen and contributing to the greater good. Yet, given the large role that work plays in the lives of American citizens, and in the lives of citizens of many other nations, it is worth reflecting on not only whether you are being a good worker (ethical, excellent, and engaged) but also whether or not your work allows you to be a good citizen.

But that’s just my story. I ask you, the reader: How do you understand good work and good citizenship? Do you see these concepts as related, or as distinct roles within your life? Has your understanding of good work and good citizenship changed over the course of your life or as you’ve held different jobs?